Festo Introduces Its Latest Bionic Robots – Spiders and Fishes and Bats, Oh My

The natural models for these three new bionic robots are the flic-flac spider, cuttlefish, and flying fox, which is among the world's largest bats.

ISLANDIA, NY, June 26, 2018 — Festo introduces in North America the latest biomimicry innovations from its Bionic Learning Network, the ongoing research project to further engineering, manufacturing, and materials science based on the study of natural systems.

The Festo 2018 bionic menagerie features a transforming spider that rolls or creeps, a robotic fish that autonomously maneuvers through acrylic water-filled tubing, and a semi-autonomous flying bat-like robot with more than a seven-foot (2.28-meter) wing span and the ability to self-improve its flight path.

The BionicWheelBot - the bionic version of the flic-flac spider

The biological model for the BionicWheelBot is the flic-flac spider (Cebrennus rechenbergi), which lives in the Erg Chebbi desert on the edge of the Sahara. Just like the flic-flac, the BionicWheelBot propels itself with a tripod gait, using six of its eight legs to walk. To start rolling, the BionicWheelBot bends three legs on each side of its body to form a wheel. The two lower-middle legs that are folded up during walking are then extended, push the rolled-up spider off the ground, and continuously propel it forward. Thanks to its integrated inertial sensor, the robot always knows what position it is in and when it must push off again. It rolls faster than it walks and can roll up a five percent incline.

The BionicFinWave navigates autonomously through a system of water-filled tubes

For the BionicFinWave, the bionics team was inspired by the undulating fin movements executed by marine animals such as the polyclad or the cuttlefish. With this form of propulsion, the underwater robot maneuvers itself autonomously through a system of water-filled acrylic tubing. Swimming autonomous robots like the BionicFinWave could possibly be developed for tasks such as inspection, measurement, and data acquisition in the water, wastewater, and other process industries. The knowledge gained in this project could also be used for methods in the manufacturing of soft robotics components.

Undulation forces from longitudinal fins allows the BionicFinWave to maneuver itself forward or backward. The fin drive unit is particularly suitable for slow, precise motion and causes less turbulence in the water than a conventional screw propulsion drive. While it moves through the tube system, the robot can communicate with the outside world via radio and transmit data, such as temperature and pressure sensor readings, to a mobile device.

The two lateral fins are molded entirely from silicone. The two fins can move independently of each other and by this means simultaneously generate different wave patterns and swim in a curve. The BionicFinWave moves upwards or downwards by bending its body in the desired direction. The crankshafts together with the joints and piston rod are made from plastic as integral components in a 3D printing process. The remaining body elements of the BionicFinWave, which weighs only 15 ounces (430 grams), are also 3D-printed; this enables the complex geometry to be realized. Pressure and ultrasound sensors constantly register the BionicFinWaves distance to the walls and its depth in the water, which prevents collisions with the tube system. This autonomous and safe navigation required the development of compact, efficient, and waterproof or water-resistant components that can be coordinated and regulated by means of appropriate software.

BionicFlyingFox - ideal flight path determined with machine learning

To emulate the flying fox, among the worlds largest bats, the wing kinematics of the BionicFlyingFox are divided into primaries and secondaries with all the joints in the same plane. To enable the BionicFlyingFox to move semi-autonomously within a defined space, the robot communicates with a motion tracking system. The motion tracking system plans the flight paths and issues the required control commands. Starting and landing are performed by the human operator; an autopilot takes over during flight. Pre-programmed flight routes stored on a computer specify the path taken by the 20.5-ounce (580-gram) BionicFlyingFox as it performs its maneuvers. The wing movements required to effectively implement the intended movement sequences are calculated by its on-board electronics. The BionicFlyingFox optimizes its behavior during flight and follows the specified courses more precisely with each circuit.

The innovative membrane covering the skeleton was specially developed by the bionics team for the BionicFlyingFox. It consists of two airtight foils and a woven elastane fabric, which are welded together at approximately 45,000 points. The fabrics honeycomb structure prevents small cracks in the flying membrane from increasing in size. The BionicFlyingFox can thus continue flying even if the fabric sustains minor damage. Due to its elasticity, the flying membrane stays almost crease free even when the wings are retracted. Since the foil is not only elastic, but also airtight and lightweight, it could potentially be used in other flying objects or for clothing design and in the field of architecture.

###

About Festo

Festo is a leading manufacturer of pneumatic and electromechanical systems, components, and controls for process and industrial automation. For more than 40 years, Festo Corporation has continuously elevated the state of manufacturing with innovations and optimized motion control solutions that deliver higher performing, more profitable automated manufacturing and processing equipment.

Connect with Festo: Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter and YouTube

Featured Product

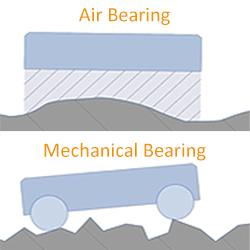

PI USA - 7 Reasons Why Air Bearings Outperform Mechanical Bearings

Motion system designers often ask the question whether to employ mechanical bearings or air bearings. Air bearings deserve a second look when application requirements include lifetime, precision, particle generation, reproducibility, angular accuracy, runout, straightness, and flatness.